Heavy Yokes of Christian Excellence

Martha Peace's Book "The Excellent Wife," The Mire of Spiritual Rumination, and The God Who Comes Looking for Us.

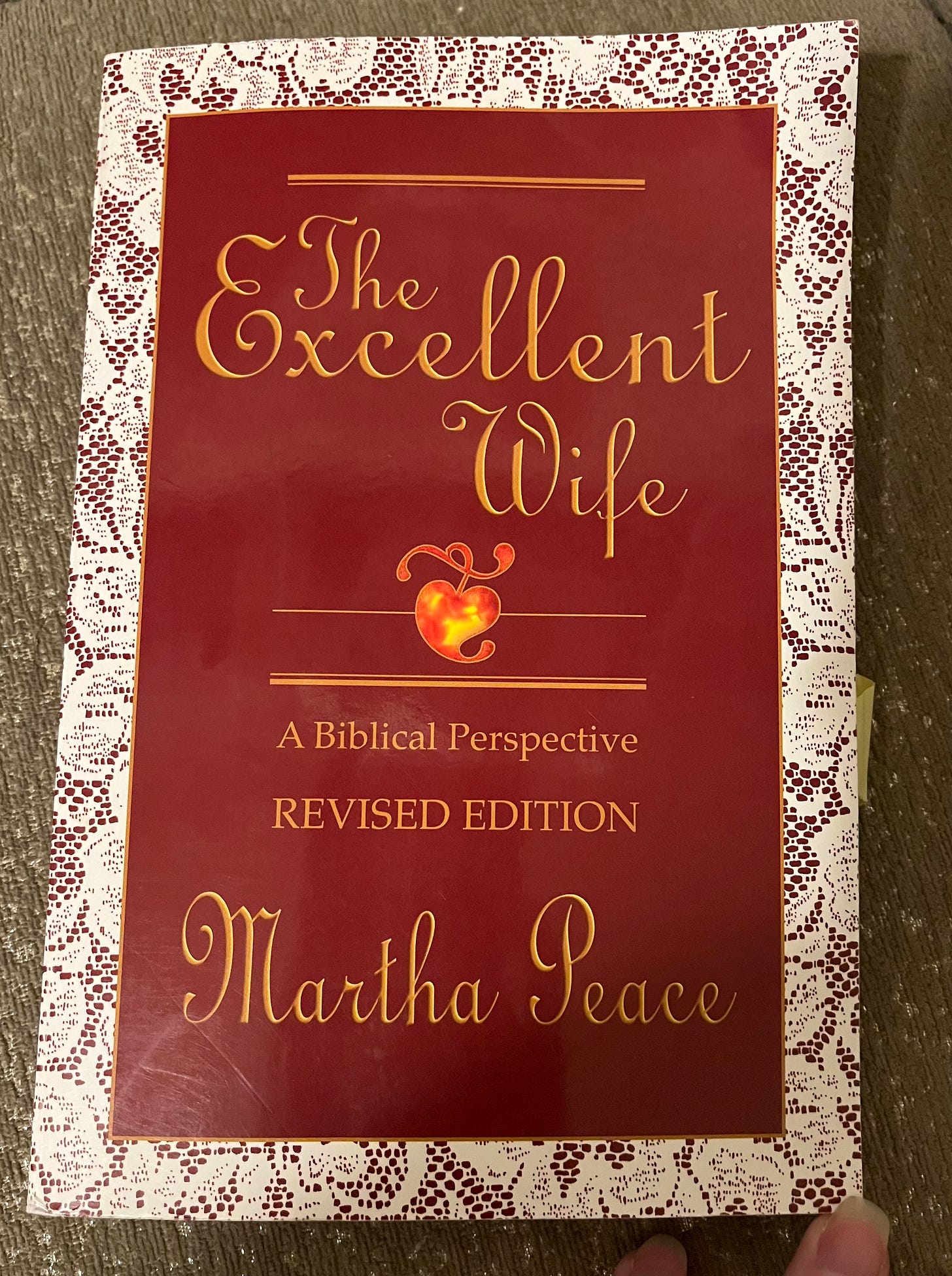

I was twenty-three years old and in my first year of marriage when my twenty-three year old husband and I moved cross country to be assistant bed-and-breakfast keepers in the Colorado mountains. Looking for community, we enrolled in the new-marrieds class at our non-denominational church. There, an older empty-nester couple split the participants into a small group of wives and a separate group of husbands. The women were assigned Martha Peace’s The Excellent Wife: A Biblical Perspective, and the men—The Exemplary Husband: A Biblical Perspective, by: Stuart Scott. I still recall circling up our folding chairs for discussion, and one of the women saying, “I threw that book across the room.” I, meanwhile, took notes, added it to my growing collection of Christian family life resources, and returned many times to its dog-eared pages in my early years of marriage.

I was employed as a teacher at a small Christian school at the time, and the married and engaged staff members were invited to a midweek evening study. This was led by a couple who probably were about five years ahead of us all in married life: two young children, a home to host us for pumpkin soup on cold fall nights, and a video-series on Bruce Wilkinson’s Biblical Portrait of Marriage: Twelve Life-changing Sessions on Building Biblical Marriages.

“The wife’s duty is to help her husband accomplish his dream,” Wilkerson taught us, and new-college-graduate me attempted to digest this pivot. Until that point, people had asked me directly about my goals and plans and hopes for the future. It was jarring and notable to suddenly disappear into the role of spouse, where Christian friends and acquaintances asked my husband alone about his seminary plans, looking right past me.

On occasional Saturdays we drove out to a little cabin where a couple who managed a ranch led us through a discussion of the new hit title The Purpose Driven Life. These teachings built on others I had received as a young adult: church Bible studies on Women in the Kingdom and teenaged years on the front end of purity culture, where youth group sermons told us how to interact with boys during dating, engagement, all with an eye toward marriage.

Reflecting back, it was . . . a lot. Three Christian-life studies in one year? Making friends, apparently, came at the cost of constant relational introspection and lessons in self-improvement. If you grew up in Christian communities, this may seem normal to you, as it did to me at the time. After all, youth ministries often focused on small groups or retreats that revolved around discipleship-oriented studies. I remember looking on enviously as my peers described older women who “mentored” them and longing for the same. You likely have your own list of mentors and resources and conferences, books and Bible studies, radio programs and video sessions and sermon series aimed at helping spiritually form you. Many of us can hardly remember a time when spiritual formation was untethered from personal improvement and self help.

And if you came to faith as an adult? Perhaps you took the fast track course in order to figure out how to do womanhood or manhood and dating and marriage and family life God’s Way. While the devotional impulses that send people to such resources are certainly understandable, they all rely on an assumption that there is a formula to be deciphered, a recipe to be followed to optimize outcomes, in this case: a Good Christian Marriage.

The Excellent Wife

“Biblical counseling”—also known as ACBC or “nouthetic” counseling—has perfected this recipe. Filled with charts about what to “put off” and “put on” and advice about how to examine your heart for idols and scrupulously tidy up your soul, nouthetic resources offer a lot for people to do. Ridding your life of what is “bad” becomes the surefire way to attain the “good.” It wasn’t until I hit a kind of personal rock-bottom that I realized the Try Harder Christian life was not Good News. But I still held on to Martha Peace’s book for longer than I’d like to admit, returning to it when circumstances or relational dynamics were difficult.

Why? Because it offered me an illusion of control. Martha is quick to reassure readers that their anger, fear, loneliness, or sorrow (all chapter titles in her book) have spiritual origins . . . and spiritual solutions. This provides an acceptable avenue of things to try for people who have been told they have no agency, that their primary choice and role is to submit to the will of another. This shows up in Christian parenting teaching that tells children to obey their parents—agents of God—right away, all the way, and with a happy heart. It also shows up in many Christian resources served up to women, where they are instructed to orbit around their husbands in every imaginable way.

I don’t think most Christian men fully comprehend the kind of catechesis Christian women receive via family life resources. Twenty-something me was concerned when my equally young husband set aside his unfinished copy of The Exemplary Husband with a shrug and a “Huh, that’s one person’s opinion.” I worried. Was he not interested enough in spiritual things? All the resources I had been given explained how husbands were to be spiritual leaders, to set the tone for the home. What would I do if my husband didn’t want to spiritually lead? (Martha et al do have answers for that, too, of course).

These Christian cultural ideals place heavy yokes on men as well, but one thing men still retain is their agency. They are told to, well, lead. They are told to act. Men are not told, as Martha tells women multiple times in her book, that if they are resistant to the message of complete submission they are not spiritually mature. They are not told their primary purpose is to fulfill the dreams of another person. They are not told to ignore any questions they might have, because “you may never comprehend all the reasons why God does what He does, but you can trust that He knows better than you what you really need. Keep in mind that you will never be what God wants you to be until you place yourself under God’s plan by coming under the authority of your husband.”1

In the same way that children are required to unquestioningly comply, Christian wives are sometimes expected to maintain a one-sided unquestioning compliance. I didn’t have a parent requiring it of newlywed me or a husband demanding it (though I want to highlight that I’ve heard from many women who were given Martha’s book by husbands who expected to be obeyed). I just had an authoritative sounding Christian teacher telling me it was what God required of me.

I wish twenty-something me would’ve had the ability to set the book aside with a “huh,” or even throw it across the room. My eventual gateway out of it was the fact that it simply didn’t work. I found myself untangling Martha’s baptized codependence in marriage counseling a few years later, where it became very clear to me that—even within a framework that a wife’s primary vocation was to be a “helper,”—self-martyrdom is, among other things, most definitely not a help. I also became a mother which enabled me to see these teachings with fresh eyes.

But two decades later, I’m troubled by the fact that The Excellent Wife still retains high reader ratings and is one of the top-marriage resources recommended to conservative Christian women. So this autumn, with a compassionate eye toward younger-me in mind, I’ve been doing a chapter by chapter deep-dive analysis of the book. This re-read was inspired by a podcast conversation I had this summer with Sheila Wray Gregoire, who critically examines popular marriage resources and their impact, and

, whose best-selling memoir A Well-Trained Wife shows-not-tells how such teaching cultivates and enables abuse and domestic violence.I’ve heard from many other women who also describe how this book kept them in abusive marriages for a long time. The underlying assumptions—that marriage will be hard, causing anger, sorrow, loneliness, and fear or that things like good health, being treated fairly, desiring a child, or seeking to have your needs met are all potential idols—are themselves kind of a red flag. It’s bleak to think about handing this off to newlyweds for it to form their expectations for marriage. I’ve even heard from women who were gifted this book as teens in preparation for dating. Each story I hear, and each reel I edit reminds me how easy it is for unexamined ideas to circulate via word-of-mouth and the recommendation of friends and pastors.

It’s even unclear how many of the ideas are original to Martha herself. In her book, she describes coming to faith as an adult and beginning to teach Bible studies shortly thereafter, all based on the teaching she had received from the pastors and Christian men in her life who were all associated with the ACBC/nouthetic counseling movement.

Because nouthetic resources show up in Christian parenting books (Tedd Tripp’s Shepherding a Child’s Heart and Ginger Hubbard’s Don’t Make Me Count to Three are two of the most popular), I’ve come to recognize both the talking points and the oft-quoted authors. Jay Adams, Lou Priolo, David Powlison, Stuart Scott—all pivotal figures in the “biblical counseling” movement of the 70s, 80s, and 90s—wrote copiously, developed curricula, and taught thousands of pastor-counselor-teachers “biblical” frameworks for solving life’s problems. These show up in regurgitated forms, and, because pastors and counselors were trained by them, the reach is exponential. In resources marketed for women, there’s often a female speaker or author positioned to teach the original talking points.

Martha explicitly addresses this: “One of the best ways to find a godly older woman is through the recommendation of a faithful pastor or church leader . . . it would be wise for churches to develop a ministry to teach the older women how and what to teach the younger women.”2 Presumably, those ministries would be led by men.

The Mire of Spiritual Rumination

So what sort of things did the nouthetic men want women to do? In short: submit. This is the recurrent theme in the book. It’s paired with anecdotes about women failing to do this as well as stories that hint that if you submit in the right way, if you are really serious about it, and if you are a real Christian, you will likely have a better marriage. Or at least you will have the reassurance that you are suffering for righteousness’ sake.

The Excellent Wife claims the authority of a biblical perspective—indeed, it is filled with countless pages of proof-texted Bible verses—but it is an unsubstantiated claim. Most often, Bible verses are used to bolster predetermined points, giving the impression that a liberal use of a concordance served these authors’ purposes. For instance in Martha’s chapter titled “The Wife’s Sorrow,” she explains that because Jesus says “Sorrow has filled your hearts” in John 16:6, the disciples must have been responding to their circumstances in sinful ways. “If their sorrow had been godly,” Martha writes, “their hearts would not have filled with sorrow. They would not have been overcome by this emotion.”3 Martha’s conclusion reads Scripture through the unquestionable nouthetic framework where overwhelming sorrow is impermissible. Rather than seeing the tenderness of this moment between Jesus and His disciples or something that lends understanding to the human experience of grief, Martha is left to force the text to fit into a nouthetic framework where human emotions are functionally equated with sin.

If a wife is anxious for her husband’s well-being, she is indulging in sinful fear, because she has idolized—or cared too much—about him. If she is grieving her infertility, she has an idolatrous desire for a child. If she desires to have her needs met in marriage, she is worshipping romantic inclinations. An irenic, almost fatalistic acceptance of everything seems to be the goal. This double-bind presents an impossible standard: a wife’s entire God-ordained role is to orbit around and serve her husband, but she must not have any personal desires for this relationship lest she indulge in idolatry. The end result is an elevation of a kind of detached spiritual bypassing, where cherry-picked religious practices are presented as coping mechanisms to achieve internal equilibrium. If things are hard, a wife must figure out how to displace unwanted emotions by “focusing on the Lord Jesus Christ,” which effectively translates into compulsively reading and memorizing Bible verses. It’s a crushing yoke.

In a chapter I recently analyzed, Martha describes how a counselee named Allison described how her husband was not affectionate, used her for sex, and never told her he loved her. He was aggravated if she tried to bring it up . Martha’s diagnosis is that Allison’s misery is a direct result of her idolatrous heart. “Whenever a wife sets her heart on her husband behaving a certain way,” Martha writes, “she will likely end up disappointed, frustrated, and hurt.4 Throughout the book, women are taught to examine their hearts (any undesirable emotion is perceived as evidence of sin or an ungodly desire), identify their “sin” according to Martha’s categories, and figure out how to displace it with a righteous habit pattern. The repetitive nature of each chapter adds to the spiritual exhaustion that comes from simply reading it.

Though the book is permeated with religious language, any conception of connected relationship with God is absent. Instead, self-initiated sin-management procedures are redefined as what it means to be in relationship with God. Even with God Himself, authentic relationship is inaccessible, and robotic emotions-management is preferred, a remarkable “biblical” choice given the robust evidence of human emotion on the pages of the Psalms and the Prophets.

The God Who Comes Looking For Us

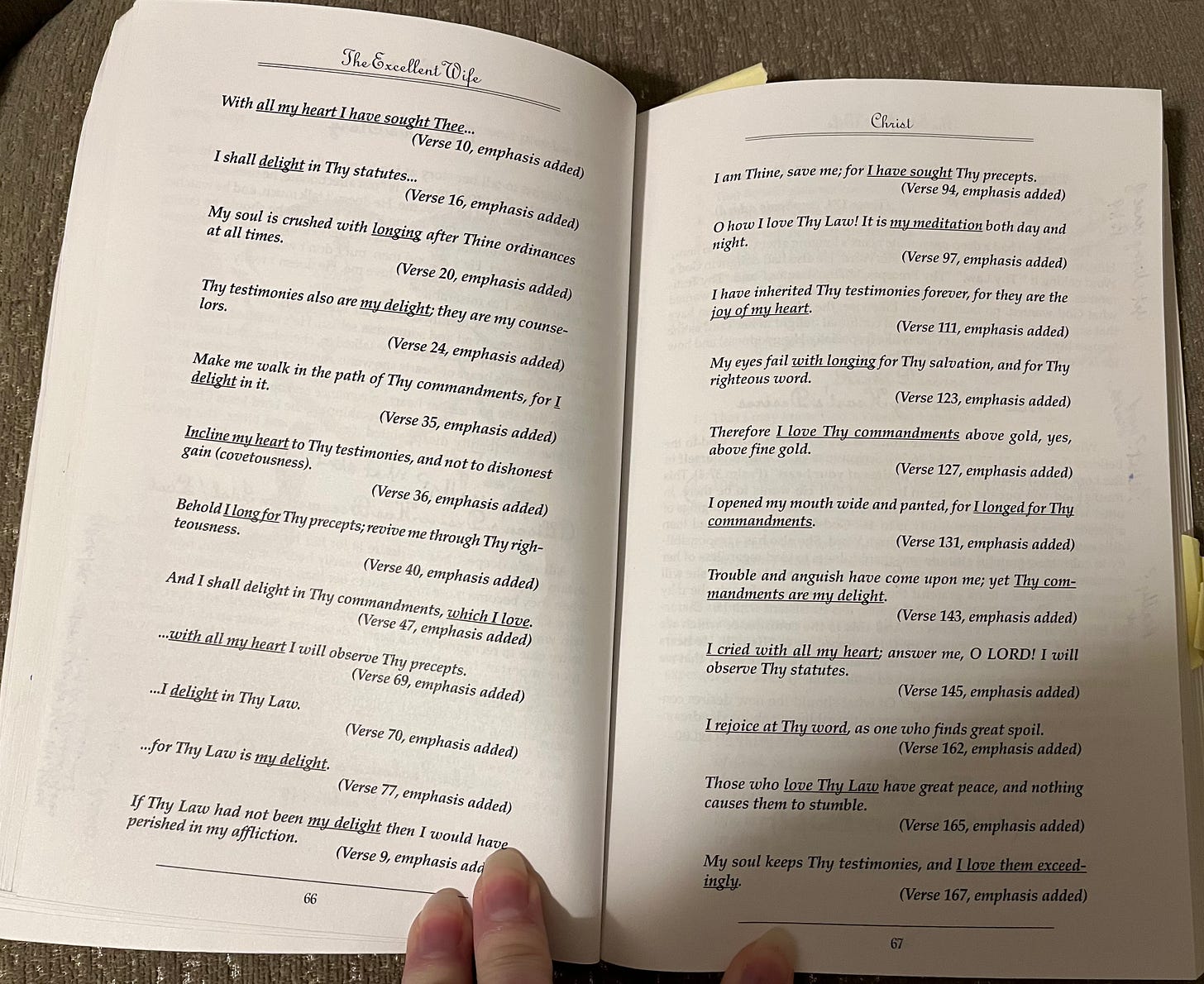

Martha does reference the Psalms when it suits, including a two-page spread of verses taken from Psalm 119 as evidence that truly mature women will be satisfied with God alone. Thus, God becomes the ultimate tool for spiritual bypassing. “What was most important to [the Psalmist] was God,” Martha writes. “The Psalmist wanted what God wanted, no matter what.”5 (Perhaps it goes without saying, but, throughout the book, Martha speaks for God, presenting “what God wants” to be her framework for marriage).

I remember photocopying that two page spread as a young wife and pinning it up where I could regularly read it as a means of redirecting my thoughts. It’s tender to revisit now. Psalm 119 remains one of my favorite Psalms, and, inspired by William Wilberforce’s example, I spent one year memorizing it. It’s a gorgeous Psalm—brilliantly composed, designed for accessible memorization via the acrostic eight-verse stanza structure. The Psalmist has much to say about the goodness of God’s law, of his desire to walk in it, of how God’s ways nourish and give life. He writes about his well-intentioned zeal, something that resonates with younger and older me. But what I find so poignant, what is so missing from Martha’s book and every resource like it, is the honest humility that comes in the final verse:

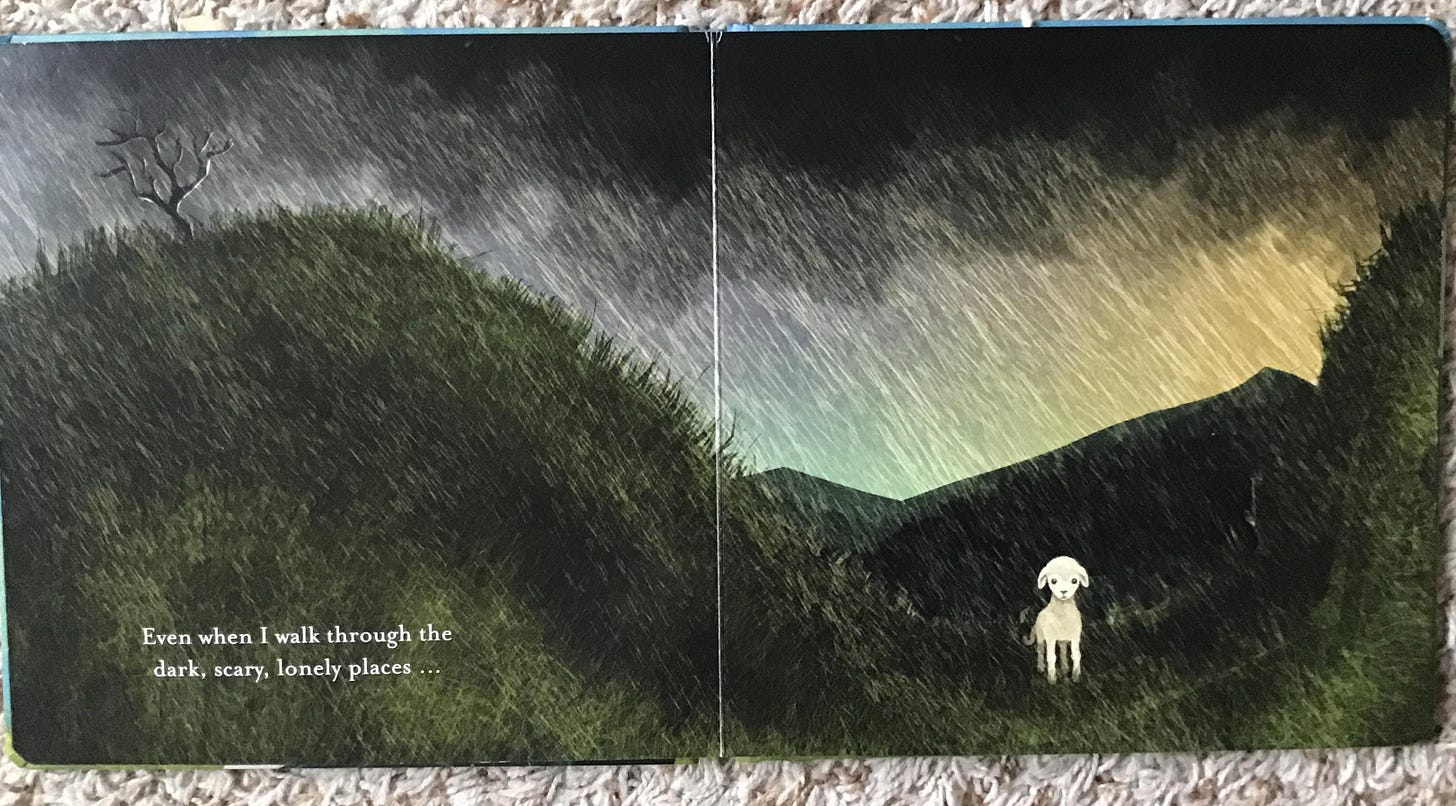

I have wandered off like a lost sheep. Come looking for your servant, for I do not forget your commands (Psalm 119:176, NET).

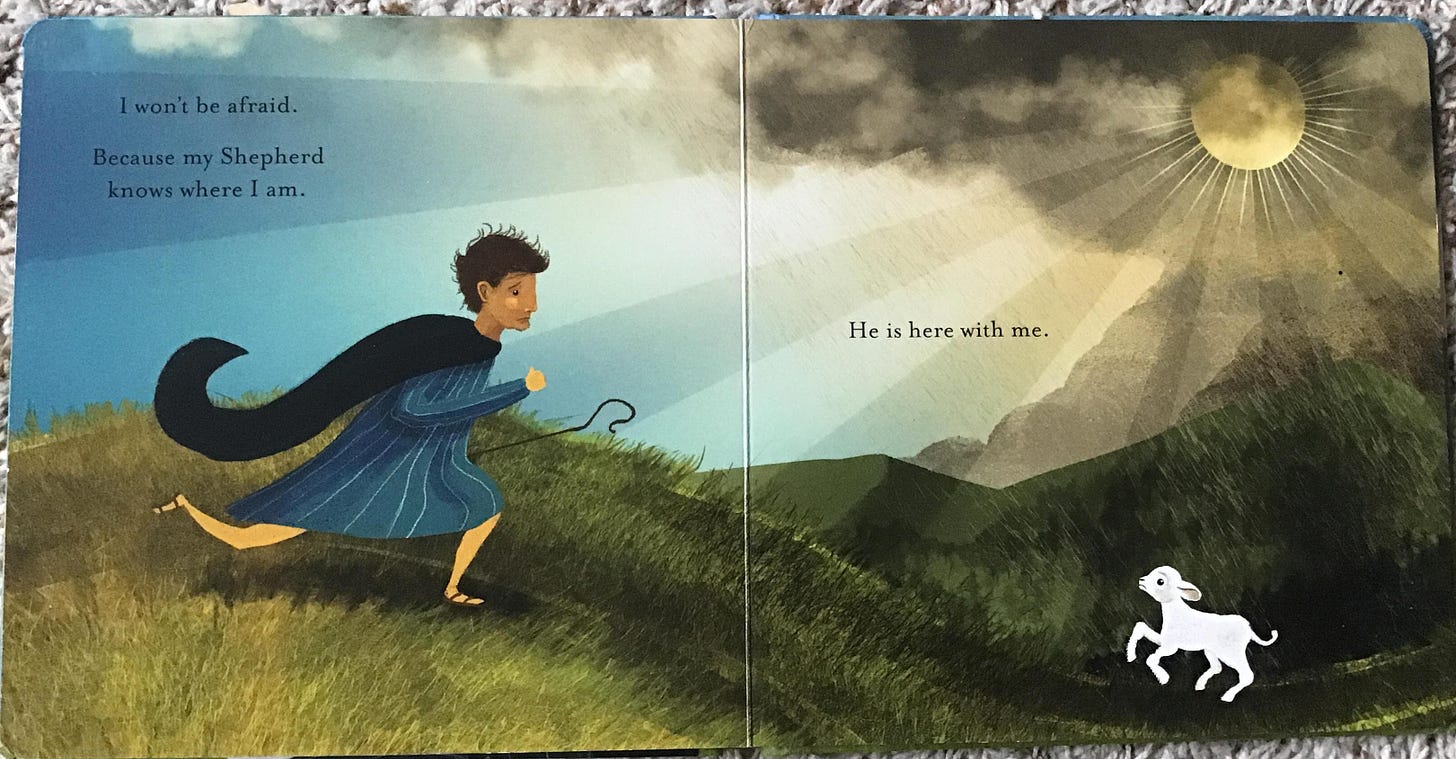

The quiet admission there, the inevitably of human failure and, yes, of human need. The inability to do it Right. The longing for the shepherd to come looking for us. The foreshadowing of grace, of the imagery that would later come, when Jesus tells of the joy God has when reclaiming the one sheep who wandered off in an echo of the imagery found in many beloved Psalms.

God delights in reclaiming lost things, no matter how lonely, scary, or sorrowful their condition. When Jesus tells the story of the lost sheep, He pairs it with one about a woman searching for a lost coin and another about a lost son, Perhaps we should retitle it as lost sons: the one son who squandered everything and the other who grumbled, “All these years I’ve been slaving for you and never disobeyed your orders.”

In Jesus’ story, the father figure seems uninterested in the excellent performance of the one, just as he seems indifferent to the inheritance which he hands over to the other. Perhaps getting it Right has never been the point. Because when the father gives the reason for His joy, Jesus repeats it twice for emphasis: “But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found” (Luke 15:24, 32)

Both sons are welcomed and loved by the father. He invites both to join the celebration and joy of a father’s love. That invitation still stands—for you, for me, for the wandering sheep, and all the people so endlessly toiling to excellently please God.

Martha Peace, The Excellent Wife, pg. 17.

Peace, The Excellent Wife, 150.

Peace, pg. 238.

Peace, pg. 65

Peace, pg. 68.

I find it really interesting how much differently my husband was affected by being around some of these teachings vs. myself. I did not read this particular book, but others of the ilk. In 8th (!) grade I did this “Bible Study” that walked through “5 Aspects of Femininity” and swallowed it whole. Perhaps certain idealistic personalities are uniquely bent towards checklist ideology, when we so badly want to do things the right way.

It certainly did me no favors when I had years of “good church girl” behavior to unlearn in order to even figure out how to name and identify emotions and find healthy ways to process them. It makes me wonder how many women just exist in a state of emotional flatness from having to squash everything down into these tiny boxes of God’s will. I was so relieved when I realized there was no scriptural precedent for emotions themselves being sinful. I’m so thankful that life became such that this framework was obviously unworkable, but I wonder how many women must become severely depressed (my own experience) before realizing this does not work.

I read and studied this book in the late nineties when I had three small children and a fraught and fractured marriage. I devoured it because I was unknowingly suffering from complex childhood trauma and was desperately searching for a formula to ease my pain. For years, I tried to erase myself based on Martha’s, and conservative Christian radio pastors’, teachings. When I finally snapped at age forty nine, I began the long hard road toward freedom and the authentic me. Thank you for this very astute and calm dissection of a book that has done so much damage to so many women. I don’t believe in banning books, but for this one, I might make an exception!