Today I’m thinking about an analogy my husband and I often use when we’re talking about spiritual drivenness & the life of grace: Quest video games vs. Sandbox ones.

If you’re not familiar, Quest games are linear, with a chronological path, achievable goals, and the kind of peril that warns: The quest stands upon the edge of a knife. Stray but a little, and it will fall, to the ruin of all.

This is in contrast to a Sandbox style game, where players roam and create within the bounds of the game, the goal being exponential exploration and creativity over completing a quest. It’s a compelling metaphor, because much of our cultural Christianity invites us to a Quest style approach: How do you find the single, Plan A path to God’s will? What are the Right Way methods needed to accomplish various spiritual goals and level up in our discipleship? This includes approaches to Christian parenting, as Hannah Anderson names so well in a twitter thread today:

The Quest approach leaves one constantly hungering for the confirmation - some kind of reassurance that says, “You are doing it right! You are on the right path! Here is your progress and status update!”

This metric also perhaps communicates a stowaway doctrine that hardship/suffering is an indication one has done it "wrong," that obstacles that impede achievement are punitive. That finding one’s self on the path to Plan B or Plan C must mean failure and divine disapproval. Such teaching can be reinforced by lessons learned early on in Sunday School classes or sermonettes from parents.

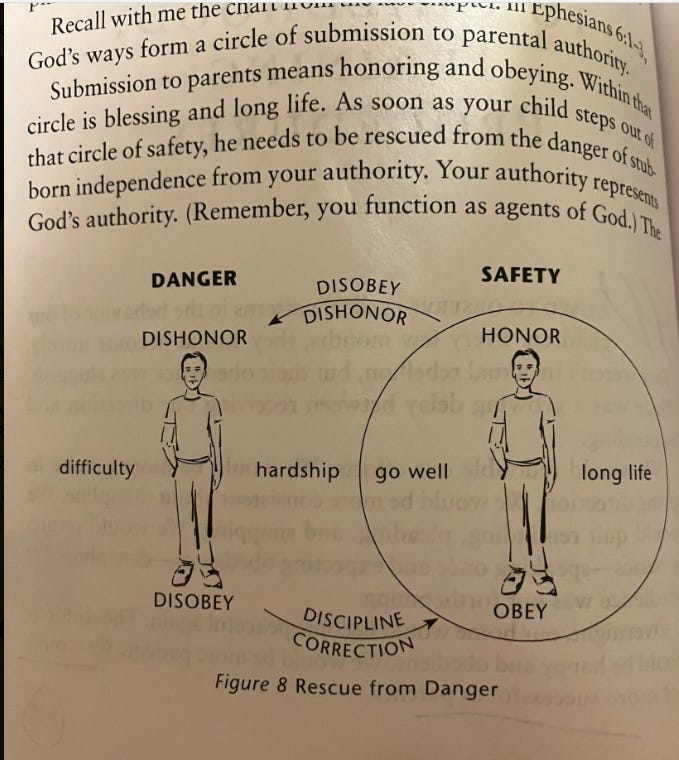

I’ve been reading Tedd Tripp’s “Shepherding a Child’s Heart” this week wherein he directly says that the primary purpose of discipline is to get your children back into a “circle of blessing” so both temporal and eternal bad things don’t happen to them. What are the long-term implications of viewing God as harsh and cruel, swift to punish any misstep?

I think one byproduct of sincere zeal in the Quest mindset can be an almost obsession with getting any element of one’s life—calling, singleness, marriage, parenting, vocation, leisure, you-fill-in-the-blank —right. I’ve written before about scrupulosity, and I think our devotional aspirations and drivenness both directly and indirectly reward spiritual achievement.

Right doctrine leads to right practice, so the idea goes, and one byproduct is a skepticism of individual perception and emotions. This week Doug Wilson & co have labeled various emotions as sin and suggested disciplining emotions is a salvation issue for parents. I’ve also been deep into Tripp’s work, where his primary focus is on the importance of parents being able to access their child’s heart in order to define their sin for them.

When these ideas grow up, they result in adults who mistrust their own emotions, intuition, and spiritual capacity, which feeds the desire to have external input and leads to ample market demand. Sincere Christians then understandably hunger for others to tell them how to get it, tailored to aspirational spiritual desires, right. The compulsion for reassurance can be soothed by prescriptives given from anyone we admire. It might come in the form of a topical sermon series given by pastors who we’ve come to perceive as omnicompetent. Or perhaps we might binge an influencer’s content and sign up for their discounted virtual course. Book publishers are happy to serve up Christian self-help, and endless streaming content offers a bottomless well of potential approval.

I am not suggesting that we have nothing to learn for others or that it is wise to become our own authorities on everything or that we default to judging ourselves by ourselves, but the determination to have an in-game status bar raises interesting questions about pneumatology & sanctification.

If Christians believe the Holy Spirit both convicts the heart of sin, righteousness and judgment, leads people into all truth, and initiates sanctification in the life of the believer, how do we envision that operating? I'm curious to hear from other Christians on how they perceive/experience this, because whenever I read the book of Acts, I'm struck by how hands off the early church leaders actually were by necessity. They traveled from place to place, staying weeks or months or occasionally years to teach and live among new Christians. The primary message was the first-hand testimony about Jesus’ life and ministry, alongside baptism and the laying on of hands. I continue to find the minimalistic approach of the Jerusalem Council remarkable given the chaotic circumstances. Every action indicates an intentional reliance on the Holy Spirit, because once the visit was over, these leaders simply sailed away, entrusting the nascent and vulnerable church to the Spirit’s guidance.

Years ago, I heard Cornelius Plantinga say something along the lines of: what we do matters, and what we do doesn't matter. It’s stuck with me, because these days I wonder what it looks like to swap out the scrupulous Questing for a Sandbox approach that trusts in both the generosity of God’s providence and the grace of His presence with and alongside us.

In contrast to many popular Christian parenting models that emphasize the importance of swift and certain consequences, I don't think God abandons us if we "get it wrong." I also don’t think he transactionally authors punitive hardship and suffering twisting the words to somehow mean that is love. Indeed, the idea that He is primarily harsh and cruel flies in the face of the One who personifies love showing us by His actions what God is like.

Stooping to become incarnate, humbling Himself to dwell among us, Jesus enters into the suffering and groaning of the world to redeem it, tabernacling among us and drawing ever nearer until we encounter the astonishing plot twist that we together become His temple & habitation. He has not left us alone to sleuth out mysterious purposes but rather welcomed us into His own body where we together take up the priestly work of being living icons and image bearers. There is breathing room in that, permission to live a quiet life loving God and neighbor in a myriad of ways without obsession.

I wonder if displacing the quest for Right Way methods with the invitation to come under Christ’s easy and light yoke would free Christian parents up. Seeking to understand and connect with the individual children providentially entrusted to parental care might displace the harried search for the right methods in order to achieve certain ends. This shift from a path marked out by aspirational ideals or fear-driven goals to a journey together ushers in broad approaches boundaried by love for God and love for our littlest and closest neighbors.

We can only offer that which we have received. Perhaps our insistence on a transactional behavioral focus in parenting methods reveals our own scarcity, our underlying doubt in God’s presence with and for us. I suppose someone in a Sandbox game can opt to play it like a Quest, creating goals to complete and milestones to mark, but it runs the risk of missing the delight, creativity, and, well, fun, of the entire enterprise.