Long ago in my pre-motherhood life, I regularly visited a mist-shrouded monastic community hidden away in the Lowcountry of coastal South Carolina. Mepkin Abbey remains one of my favorite places on the planet—and this in spite of the morning where I meandered near the shoreline only to do a panicked about face as I stumbled across a twelve foot alligator.

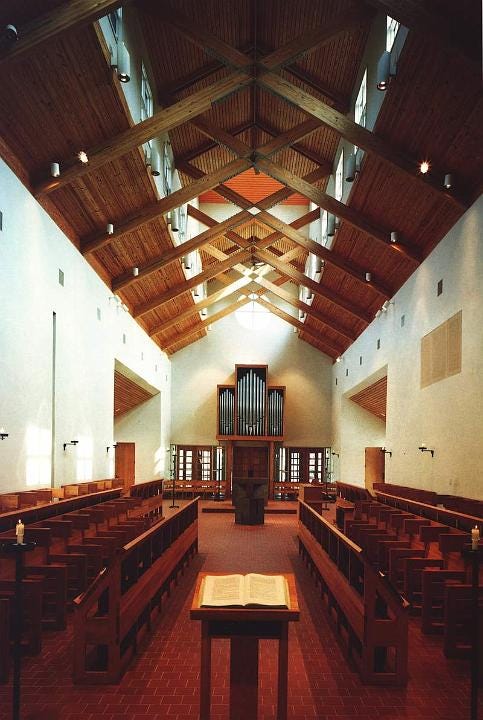

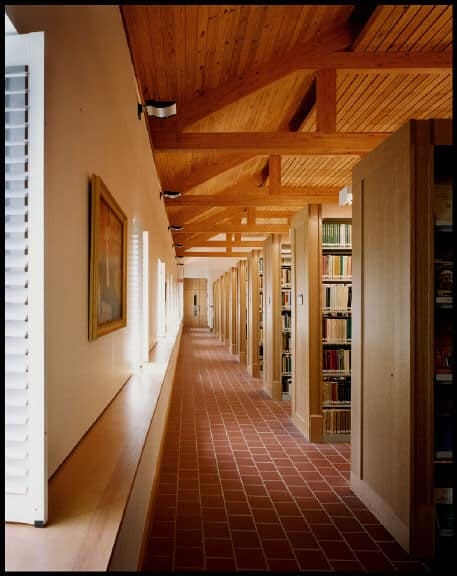

I love the monastic invitation to “come away by yourself and rest for awhile,” to embrace the solitude of the library and gardens, and to join the community for the Liturgy of Hours. To this day, the smell of frankincense takes me back—a hurried pre-dawn walk to the church for Vigils, the weight of the heavy door opening and then thudding closed to enfold me in a palpable silence scented with spices, and the richly layered baritones of the monks chanting the Psalms.

The first November I visited, I went for a week and cried when it was time to leave. Over the years, I squeezed in shorter retreats as often as I could, and occasionally my husband Aaron and I would go together. One surprising feast-day weekend, we were delighted when the monks invited guests to join them for beer and a movie.

Trappist monasteries prioritize a ministry of hospitality, which means retreatants are included in certain community practices like the Liturgy of Hours. During my stays, this involved five set times for prayer and singing. I first learned to sing the Psalter at Mepkin, and it was also where I first learned to read the Scriptures in community.

Nowadays Mepkin has a retreat center, but twenty plus years ago they hosted guests in an assortment of properties: a tidy mobile home, a cluster of rooms near the church, and a small mid-century house with several bedrooms, a shared bathroom, and a kitchen for making coffee and tea. My first visit I stayed in the latter, breaking my solitude with a rusty “hello” as I encountered other women in the tiny hallway.

We all walked to the refectory for meals, nodding at each other in the quiet of the guest dining room, where bread, cheese, and pickles were laid out for breakfast. The monks prepared delicious vegetarian meals for lunch and dinner, but these were taken in silence too. After everyone was served, the glass doors between the monastic dining space and ours were thrown open, so we could all listen to the reading of the day.

Across the way, the monks sat on wooden seats around a long table that filled the room. At its head, the chosen reader opened a book, and, while we nourished our bodies, his voice nourished our imaginations and souls. I don’t remember what books were read on every retreat, but during that first one, I joined the community midway through Anne Rice’s Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt.1

Mepkin was spiritually formative for me in countless ways, but the practice of reading in community stuck with both Aaron and me. More than a decade later, mirroring the monk’s hospitality, we began to host a weekly dinner, where we squeezed as many chairs as possible around the table in our small dining room, invited friends, and passed the Bible around.

For the entirety of the meal we took turns reading aloud, sometimes finishing whole books in one sitting which is a powerful practice all on its own. And there was something extraordinarily lovely about hearing the familiar words read by brothers and sisters, one after another—people who came to be dear friends. We blustered our way through the geneaologies. We laughed and theorized about whatever “because of the angels” could mean. And we sometimes simply digested the readings in silence.

All of it was done in the moment. Guests tossed out suggestions for the readings, and we dove in. There wasn’t a prepared list of discussion questions or a point-by-point outline. The reading wasn’t a precursor to a Bible study. The reading itself was the spiritual nourishment, and the conversation that followed was a spiritual potluck of sorts, where everyone could share reflections . . . or not . . . as they pleased.

There is a long history of collective reading in the Church. Some of this is due to necessity; both literacy and access to one’s own personal Bible are historical luxuries. But communal reading was practiced long before Christianity. Jewish religious practice involved corporate reading; we see it on the pages of our own Bibles, when Jesus unrolls the scroll in the Synagogue and reads the portion for the day or even earlier when the gathered people of Israel listen to God’s Word read aloud.2

This is one reason why the Church throughout the ages has included Scripture reading as part of Sunday worship. In many churches today, this is arranged according to what’s called a lectionary, a calendar of Scripture passages appointed for each Sunday. These lections typically include one passage from the Old Testament, one psalm, one reading from the epistles, and one segment of the gospels. At a set time during the Sunday liturgy, parishioners read the first three of these aloud to the seated congregation, after which we all stand to receive the gospel read by a minister, which is followed by a sermon on one or several of the lections.

I love so many things about the lectionary. It allows me to hear the voices of brothers and sisters regularly. It connects me with the global Church, where Christians across countries and denominations read the same passages that day. It provides boundaries for preachers and removes the compulsion for preacher-selected topical sermons. And it ensures a regular corporate reading of the whole of Scripture. If a church continues on through the three-year cycle of assigned readings, they will, at the end of it, have spent time together in every book of the Bible, often revisiting certain passages several times.

The brilliant people3 who arranged the lectionary also took into account the church calendar, so some appointed readings touch on seasonal themes and feast days. And, in the same way that the seasons are redolent with holiday traditions, I now find that the turning pages of the Church calendar come accompanied by memories of certain Bible passages. When Lent arrives, I am ready to walk with Jesus in real time through the lessons. When the long days of summer sprawl out in front of me, I welcome the longer stretch of narrative portions. When the days grow short and darkness lengthens, I am eager to hear Advent’s promises of Christ’s return.

The lectionary, too, has formed me spiritually and continues to do so. When COVID hit, Aaron and I missed our Table Talk dinners. We live in Washington state so that first long year of Zoom and YouTube church gatherings stretched into a second that still held many restrictions. While our parish adventurously gathered in all kinds of unconventional venues, we missed the closeness of in-home connection and decided to see if there was a way to still feast on the Scriptures together. We thought a podcast might allow for some of that connection to happen virtually, and Aaron hoped that our conversation might be a help to other pastors in the early stages of their sermon preparation.

In a house with eight people and two cats, lockdown and the months following were never exactly quiet for us, but one night a week we put the youngest children to bed, shut ourselves in the room we were using for remote/home-schooling, and recorded the first episodes of the At Home With the Lectionary podcast.

I recently revisited those earliest episodes, and the echoing audio and occasional meows took me back to those days where we missed and longed for our community. We set out to connect with our parish friends, little expecting that it would be so personally nourishing for us to set aside a weekly hour (or sometimes two) to simply sit with the Scriptures and discuss them as friends.

I’ve been doing quiet time in some capacity since twelve-year-old-me cracked open my first prayer journal, and I don’t regret a minute of it. Personal reading and Bible study has also been spiritually formative, but I’ve discovered that live, unscripted conversation sparks different thoughts. The way a friend sees a passage is sometimes different than my own, and their thoughts invite me to try out a new pair of glasses and come to the text with fresh perception.

We’ve now been podcasting for three years, week in and week out spending an hour in Scripture, finding our own monastic rhythms. We’ve heard from people who join us as they drive or bike into work, who listen during their daily jogs, who invite us along as they tidy up or wash dishes or fold laundry, and from some who carve aside a space for quiet: they light a candle, make some tea, and settle in for reflection. Some people listen in advance of Sunday morning and others join to reflect back throughout the week. I love imagining all of these scenarios! It’s been such a grace to join so many brothers and sisters, and I only wish I could sometimes hear *their* voices reading the passages as we sit ourselves down to the spiritual meal God has prepared for us.

This week marks the completion of the 3 year lectionary cycle and the beginning of a new year according to the church calendar, but we aren’t ending the podcast. We’ve grown too attached to the practice now. These days, we record on Sundays. So sometime in the early evening, Aaron and I brew some coffee and head up to my home office wedged inside a large bedroom closet, where we pull out the microphones, jot down the assigned passages, and rustle through the crinkled-pages of our Bibles as we read and discuss together.

Starting this week, with the readings appointed for Advent 1, Year C, we’ll reach for a new lectionary, the one found in the 2019 Book of Common Prayer.

We’d love for you to join us. We want to welcome you into our home and conversation but, more than that, we hope that you’ll find yourself at home with the lectionary, too.

Until then, friends, it’s nearly the eve of Advent, so . . . Happy New Year!

Listen to the Season Two trailer for the At Home with the Lectionary podcast:

If you can get your hands on the sequel, Christ the Lord: the Road to Cana, it’s well worth a read, and the audiobook is fantastic.

See Luke 4 or Nehemiah 8 for examples, though public reading was practiced throughout the festivals and feasts of the people of God in Israel.

After the Second Vatican Council, the Roman Catholic church produced a lectionary that became a template for many other overlapping lectionaries, including The Revised Common Lectionary—used by 20+ Protestant denominations. I love the ecumenical potential and unity here!

Many prayer books also include a daily lectionary, something that might take you through the Psalms in 60 days, alongside a breadth of the rest of Scripture over the course of two years. I love that the Dwell audio app now has a track for these readings.

This is lovely. I'd love to visit a monastery someday. I'm unfamiliar with the lectionary, but I'll give the podcast a listen!

I'm looking for something to listen to as I knit and I'm excited to give the podcast a listen!